Could North Sea Oil & Gas boost UK economy?

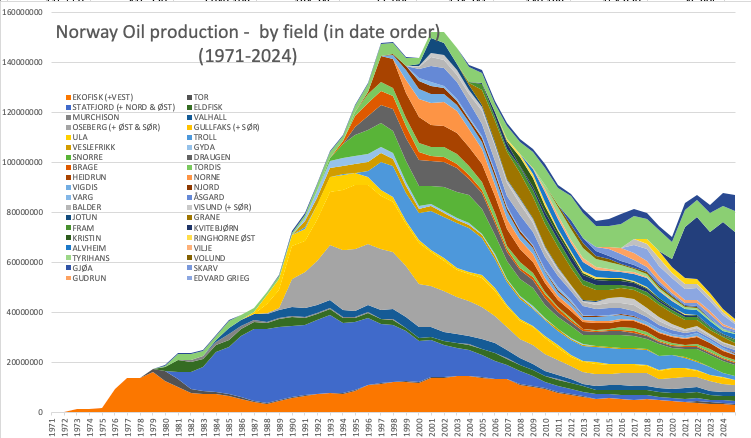

Norway's oil wealth is the envy of the world.

Its gas exports prop up the whole of Europe against embargoed Russian supplies, and this tiny nation ranks 12th in the world for oil production.

Why can't the UK emulate Norway's model?

As Norway-envy reaches fever pitch, some UK politicians have jumped on the bandwagon with pledges to tear up 'net-stupid-zero’ policies, to emulate the Nordic dream with our own unlimited riches.

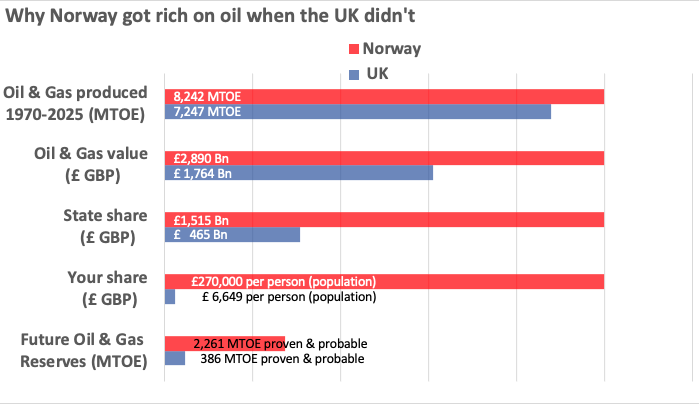

But this confected narrative to woo the populist vote is at odds with hard inconvenient facts, like: (a) profitable oil and gas has gone; (b) the UK sold its assets in the 1980s, but Norway still manages its own resources and keeps the profits; (c) any spoils would be spread much more thinly, among a population 12x bigger than Norway; (d) the UK public can’t afford to stay hooked on oil and gas... The list goes on.

How Norway Got Rich . . . (and why the UK can't)

Five ways that Norway's Oil & Gas differs from the UK:

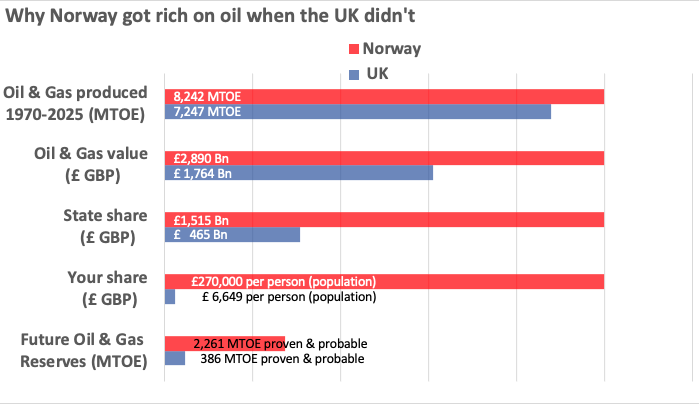

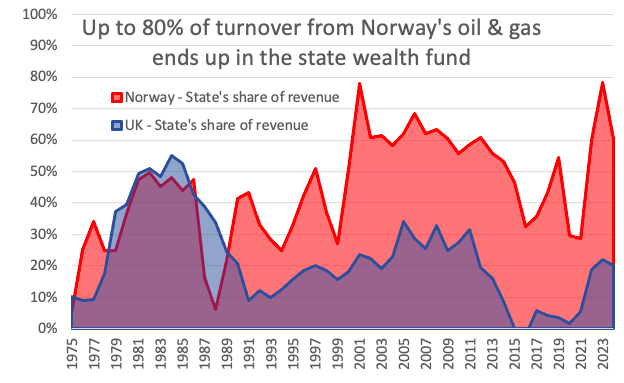

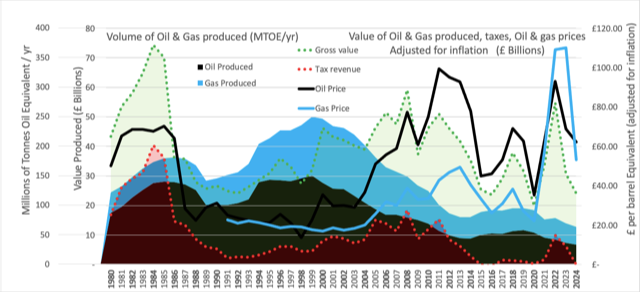

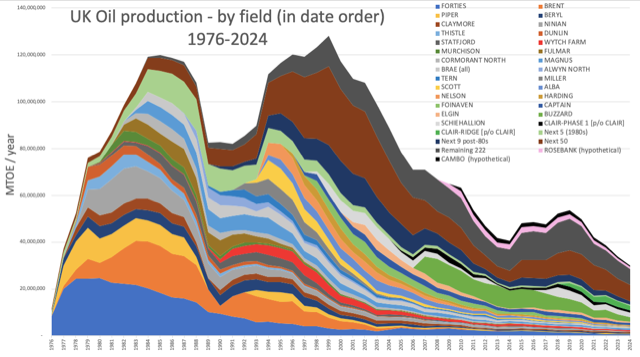

Chart 1: Why you don't feel oil wealth like Norwegians

Data sources

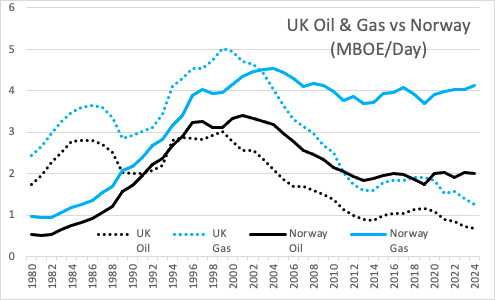

- All-time production totals for UK and Norway are very similar - 8,242 MTOE for Norway compared to 7,247 MTOE for UK. Norway is world's 12th biggest producer, whilst UK still ranks 20th.

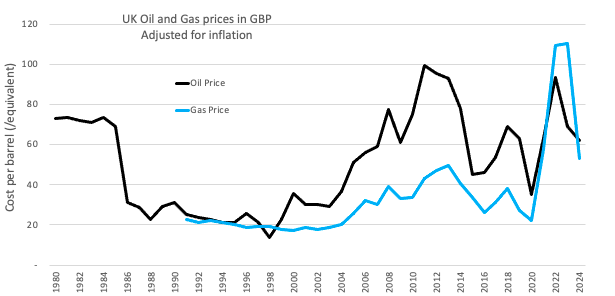

- UK produced and sold its product when prices were low - UK production was at its height in the 1990s when oil prices were really low ($10-20), whereas Norway benefited much more from soaring oil prices after 2000 (>$100). [More on this below]

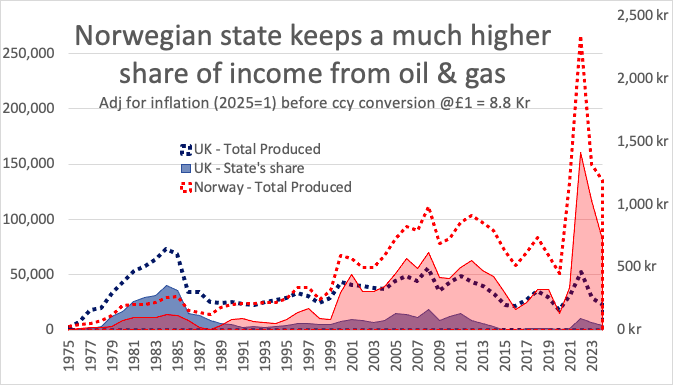

- UK state gets a much lower cut of the revenues than Norway - UK sold off all its interests to private operators in 1986, and demands little in tax or royalty. In contrast, Norway profits from the major stakes it retained, which also give it maximum control over operations to manage resources for the long term. [More on this below]

- Norway has 5 million citizens compared to UK's 70 million - This alone makes Norwegians 12x richer. Any spoils in the UK get shared more thinly across a much bigger number of citizens.

- Last but not least... The easy oil and gas has gone. What's left faces costly challenges, which depend upon high oil prices just to break even. [More on this below]

More ways that the UK case is different to Norway's

- Norway is not hooked on its own oil and gas. Most of its domestic energy comes from its hydro-electric riches, so nearly all the oil and gas is for export. The UK depends on pricey gas for electricity, and even more for heating homes. We can't wait four years for new gas fields to come on stream in the vague hope that it will plug the gap for 5 years. By that time, demand for gas should be much lower if UK and EU governments hit their renewable energy targets

- The UK’s remaining reserves are only viable when oil and gas prices are high - high prices help oil companies, but really hurt the UK public and the wider economy. Lower oil prices would kill UK production (as US shale oil producers found out to their cost in 2025, at $70 a barrel, which is not even that low historically). Moving away from oil and gas will substantially bring down UK energy costs.

Is Net-Zero to blame for North Sea decline?

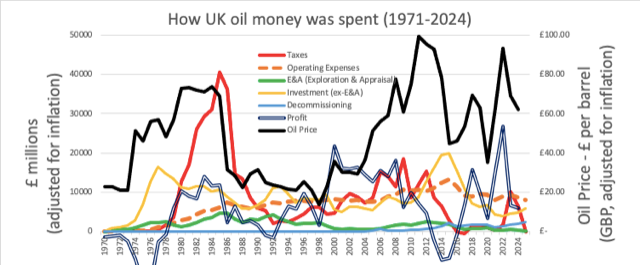

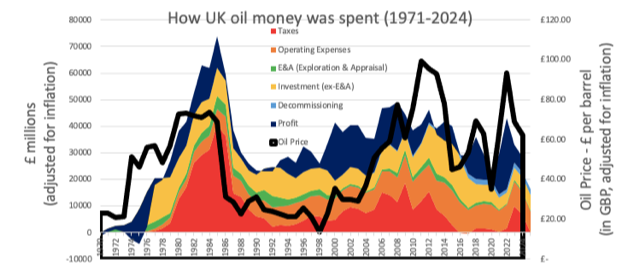

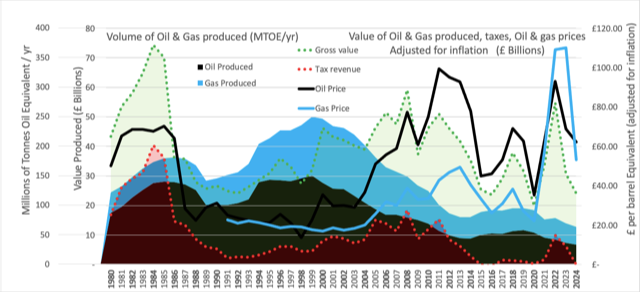

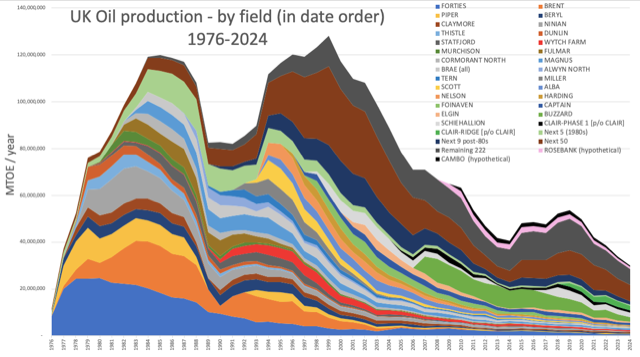

No, absolutely not! Production peaked in 2000, then collapsed by 70% in the following ten years. This was all the more startling, as it happened just as profitability soared on the back of a 10-fold increase in the real-terms price of oil. Charts 2 & 4 show that the timing of this collapse had nothing to do with either an adverse economic environment (profits were at record high levels) or net-zero regulations (There was political pressure to reduce emissions, but this was focused mainly on coal. The first UK legislation to target carbon emissions didn't come into force until 2008).

Chart 2: Profits soared (green line) as oil price sky-rocketed (black line), but it couldn't stop it couldn't halt the slide from 2000 peak.

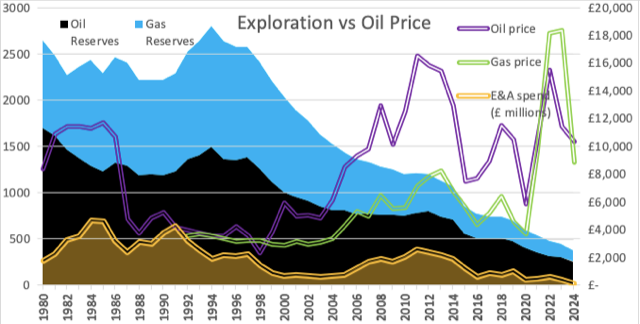

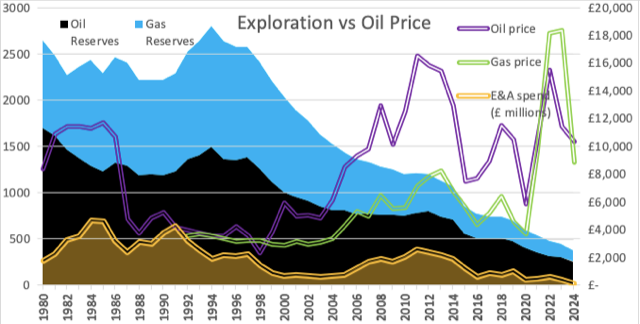

Chart 3: Exploration spending tripled when oil prices peaked around 2010, but it made little difference to the downward trend

Chart 2: The UK sold most of its oil in the 1990s at $10-20/barrel, but there was nothing left to sell when prices hit $130 in 2007, a ten-fold increase in GB £ real terms. Sky-high prices produced soaring profits that masked the 70% fall in production from the 2000 peak, until world oil prices collapsed after the 2008 financial crisis.

Data from

NSTA,

UK.gov,

UK.gov,

US EIA,

Macrotrends.com

Oil companies tried to save North Sea Oil

Charts 3 and 4 show how oil companies poured investment into the North Sea to try to turn things around. Real-terms E&A spending (Exploration and Appraisal) rose five-fold from £570 million in 2002 to £2,534 in 2011, in the search for new fields. Investment in existing fields quadrupled to 20 billion in an effort to 'squeeze every last drop out' of existing fields.

Government also tried to save North Sea Oil

Yet more evidence that the collapse was not politically motivated comes from government efforts to boost the sector when its record profits turned to losses. The global financial crisis of 2008-2012 hit oil prices and North sea profits hard. Chancellor George Osborne responded with cuts to duties, abolishing taxes altogether in 2016, in an effort to stimulate growth. As a result, operators paid almost nothing to UK tax payers from 2016 (chart 5), until the Jeremy Hunt brought in the 2022 windfall tax.

What happened to the Oil?

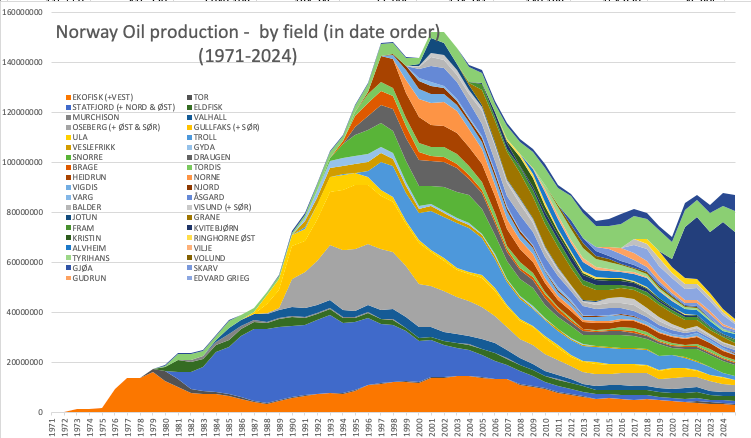

Why did Britain lose its oil, but Norway is still producing?

Neither sky-high oil profits nor generous tax breaks could bring in more big discoveries to keep the pipelines flowing. The oil really had gone. This is primarily down to geology, that the UK’s huge fields had all been found, and anything left is much less accessible - in deeper water, more remote, in fragmented or otherwise difficult reservoirs, with viscous oil, low field pressure etc.. Some of it could still be recovered when oil prices are high enough to cover the extra costs.

In contrast, Norway’s peaked later and then held steady (see chart 1) just as prices soared (chart 2). Norway also claims that tight state control over its assets enables it to overcome 'market failures’ (where private enterprises' priorities conflict with the public’s best interests). This allows government to better manage production for the long term. Private operators in the UK sector were free to max out on oil & gas, then sell their assets on to smaller operators as they pulled out.

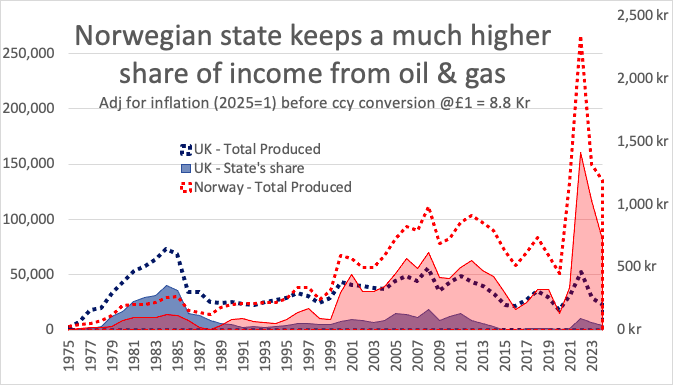

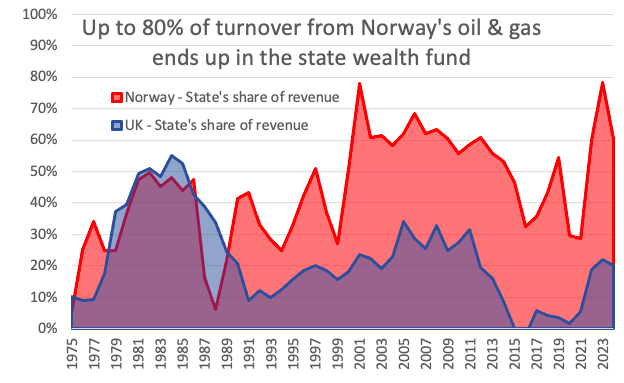

Unlike the UK public, Norwegians benefit from oil & gas wealth

Chart 10 & 11: While the UK privatised its oil giants BP and British Gas in 1986, Norway chose to retain its share, and now benefits from much higher share of the spoils.

Data sources

Thanks mostly to the 'windfall tax' imposed in 2022, UK tax receipts from oil and gas amount to £25 billion for the whole of the last 10 years. That's about £300 per UK citizen. In contrast, with its tiny population, each Norwegian has a $360,000 stake in the sovereign wealth fund, now valued at over $1,800 billion. This is because a much bigger share of the profits end up in government coffers. Producers in UK waters paid virtually nothing to government from 2016 for the oil & gas they extracted from UK waters and sold at record profit, until the windfall tax helped claw something back as UK tax payers suffered record bills for their energy.

Even though we 'share the same sea bed', Norway happens to have the bigger oil and gas fields, that remained productive when oil price was high. The UK's oil and gas fields all ran out during the era of cheap oil, and now most of what remains is very difficult (expensive) to reach.

How much oil is really left?

'Kick-starting' the UK's oil & gas sector will NOT solve the UK's energy problems

Actually, there is some oil left, and in 2025 the UK still ranked amongst the world's top 20 producers (just), compared to Norway in 12th. There are even numerous undeveloped oil and gas fields - most notoriously Rosebank and Cambo. Both of these latter two fields, discovered in 2006 and 2004, remained undeveloped for 15 years because they were deemed too costly and risky to develop under previous owners.

Chart 7: Compare the massive output from the UK's big early oilfields to the very small impact that Rosebank and Cambo (in in rose-pink and black, top right of chart) would have made if they had been developed.

Data from

NSTA

Chart 8: Norway's giant fields were exploited more gradually than the UK's

Data from

Norwegian Offshore Directorate

These two are huge UK fields by today’s standards, with 300 and 200 million barrels respectively, but they’re minnows compared to the giant fields that changed Britain. Chart 7 shows UK oil production by field. The giant Forties and Brent fields produced 10-times more oil respectively than Rosebank and Cambo’s recoverables. The last two lines on the chart are hypothetical additions to represent Rosebank and Cambo - in rose-pink and black. They illustrate the potential contributions the two newcomers could have made to overall UK production if they had been exploited. Developing them will not bring back the good times, or even halt the decline, but it would send a very bad signal to the rest of the world, that the UK places its own petty short-term gain above any international collaboration to avert the global consequences of the fossil fuel industries.

Who will pay to 'squeeze every last drop of hydrocarbon out of the ground'?

There is actually much more oil under the UK seabed than could ever be recovered. Most of it is the inaccessible remains of old oilfields that slowed to a dribble many years ago, but there are also many fields that were never exploited because they were simply too expensive to develop. A good example is the vast Clair field with 8 billion barrels of oil, discovered in 1977, but only now being exploited because it’s so difficult and costly. Geologists estimate that 650 million barrels are recoverable (about 8% of the oil-in-place) because the field is highly fractured in low-porosity sandstone; the oil doesn’t flow easily because it’s viscous with little pressure; and the location is costly, 50 miles from shore, under the stormy Atlantic Ocean towards Iceland. The first phase has been targeting 200 million barrels since 2005, while the second phase didn’t start producing until 2018 with the help of high oil prices and 100% tax breaks. There are many other smaller undeveloped discoveries that are only viable with tax-payer’s help. But whether tax payers could actually benefit from these fields is a good question.

Who will pay high cost for UK oil & gas?

The UK now produces less than half of its own oil and gas, and the huge reserves that used to underpin the UK economy have now nearly all gone. Politicians that blame net-zero zealotry and over-regulation ignore the evidence to fire up their audience with false hope. What remains of the UK’s oil and gas is only viable when prices are high. But when prices are high, the UK public and the wider economy suffer. That's a good reason to wean ourselves off hydrocarbons. Alternatively, when prices are low, the North Sea isn’t viable, and we have to import our energy. And that's another good reason to wean ourselves off hydrocarbons.

Prices are so low right now that even the US shale oil boom has become uneconomic. Operators there are shutting up shop. Analysts forecast that prices will remain low for several years as OPEC increases supply to claw back market share. Factor in that China and India are decarbonising fast, and the demand for hydrocarbons could even begin to decline. Why would anyone actually want to start developing risky, challenging, costly oil and gas fields right now?

UK not in 'absurd situation’ of leaving vital resources untapped whilst Norway grows rich by extracting them ‘from the same seabed’

An absurd situation would be to flog a dead horse whilst still importing costly hydrocarbons, when home-grown renewables have become so cheap. The easy oil has gone, and what's left is marginal fields that need high oil prices and tax help to become profitable. Instead of making impossible promises, we should be investing in an affordable, durable clean energy future, and managing the prospects of oil and gas workers, helping them to transition to new careers in the new industries that are also crying out for their skills.